Willy Ronis: Photographies 1934-1998

Casa dei Tre Oci, Venice

I visited this exhibition while on a short visit to Venice in December 2018.

The exhibition was described as “the most complete retrospective of the great French photographer to be held in Italy, featuring 120 vintage images, among which about ten previously un-exhibited ones devoted to Venice, together with documents, books, and letters never previously shown… The exhibition ranges over the whole career of one of the major interpreters of twentieth century photography and a protagonist of the French humanist tradition.”

The notes accompanying the exhibition indicate that Willy Ronis was born in 1910 and died in 2009. His mother was a piano instructor and his father had a photography studio in Montmartre, Paris. Ronis was interested in music and initially planned a career in music. However in 1932 on completing his compulsory military service, he was needed to run his father’s photography studio as his father was suffering from cancer. After the death of his father the business closed and Ronis began working as a freelance photojournalist until 1940 when he left Paris to escape the German invasion. He returned to Paris in 1946 and he joined the Rapho photo agency (an agency specializing in humanist photography). In the early 1950s, he became known internationally for his commissions for Life and other magazines.

The exhibition included 120 images made by Ronis over a 64 year period. As such there was a great deal of content for me to assimilate.

I have made extensive notes about the exhibits, but to focus my learning will describe here three aspects which I regard as my key learning points from visiting this exhibition.

1. Editorial Control of Output and use of images

Ronis had strong views about the use of his images and the depiction of his subject matter in publication. He resigned from Rapho for a period when he objected to the captioning by The New York Times to his photograph of a strike (“Willy Ronis” by Peter Hamilton, in The Oxford Companion to the Photograph, ed. Robin Lenman Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005; ISBN 0-19-866271-8).

Of note also is that he objected to the cropping of one of his images for publication in a British journal. The image “The delegate, strike at the Charpentiers de Paris, Paris” (below) shows a trades union representative addressing strikers in 1950. However when published the right hand side of the image was cropped, removing the delegate. This changes the image and what it appears to show. Before cropping it showed strikers listening attentively to their representative; cropping it appears to show a mob without that direction and leadership.

I found this very clear and stark example of how simple changes to an image alter its interpretation and therefore, meaning. As photographers we need to be explicit about any such manipulation of the image to create the effect and meaning we want. When this is outside our control we have to be wary our work still shows what we intend.

2. Emotional contact with his subjects

Many of the photographs made by Ronis in Paris show his subjects facial expressions very clearly. This in turn appears to show some emotional contact with them which is communicated through the image.

Examples of this which stand out to me are:

Le petit Parisien, 1952. The boy is smiling broadly, we can sense his happiness from his expression.

Conversely the man pictured in the Christmas shopping, Semaine de Noel, place du Palais Royale 1954, is clearly not enjoying himself unlike the others around him.

A third image, of a Miner Suffering with Silicosis, Lens 1951, shows a clearly sad man. However Ronis has chosen to photograph him through a window. It seems as if this barrier represents a separation of the miner from his work and colleagues because of his illness.

What I think I learned from these and other images is the importance of capturing the facial expression in these informal portraits and thereby communicating some emotional contact with the subject to the observer.

3. Ronis’s self-perception as shown by self-portraits

There were five images in the exhibition which were self-portraits by Willy Ronis taken at different stages in his career. I thought these images depicted aspects of himself which he wanted to emphasise at these different stages. They appear to show his interests and activities at various stages in his career.

I was unfamiliar with all the work of Willy Ronis when I went to the exhibition, but writing up these notes I became aware of many other self portraits. This made me realise that the exhibition was curated and the views opinions and attitudes of the curator influence the choice of exhibits. Thus my perception of Ronis as I learn it from this exhibition is coloured by what the curator chooses to show me. It is with this caution that I describe what I think I learned about Ronis’s self-perception and how he chooses to show himself to the world.

The earliest image was from 1929 and shows a young Willy Ronis in the dining room of the family apartment. He is studying a music score and has his violin under his arm and his bow in his hand. It is a very formally composed image: he is smartly dressed, looking studious, and on a side table behind him is a water jug and glass.

The reports of his life story indicate that at this stage in his life he was serious about music and intended to pursue this as a career. I interpreted this image as him showing this interest and wonder if he took this for posterity so that when as a successful musician it would show his early interest and activity in this area. It is ironic that this is however the early image of a great photographer – rather than a musician.

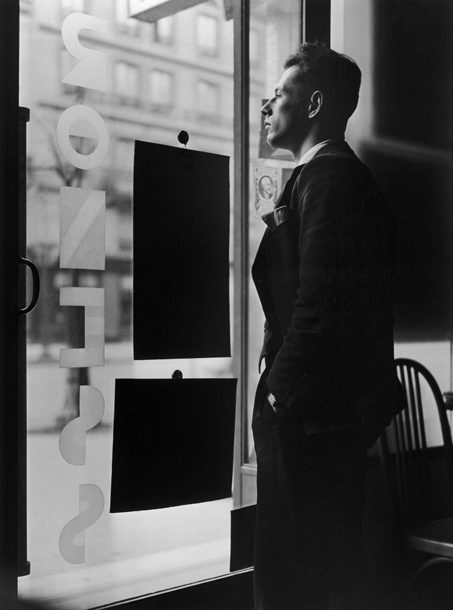

The second image in the exhibition is from 1935 and shows Ronis in the window of what had been his father’s studio which he now ran.

He is smartly dressed in a suit and looking out of the window. He has a confident stance, erect and looking straight ahead. He is now businessman running an established business premises. The appears to present himself as well-to-do successful and respectable businessman.

I was struck by the composition in this image. Because the image is taken from inside looking out of the window, notices in the window become black shapes, the left side of the image is also black with little detail and the body of Ronis in his dark suit provides a dark shape to the right side of the image. I am probably over interpreting this, but during the same weekend I visited the Peggy Guggenheim collection and saw Miro’s Femme Assise II, 1939 (below). The Miro is composed of shapes of black with small areas of detail.

Although painted after Ronis made this image, I wonder if the influence of some of Miro’s earlier works had led Ronis to compose this image with blocks of black.

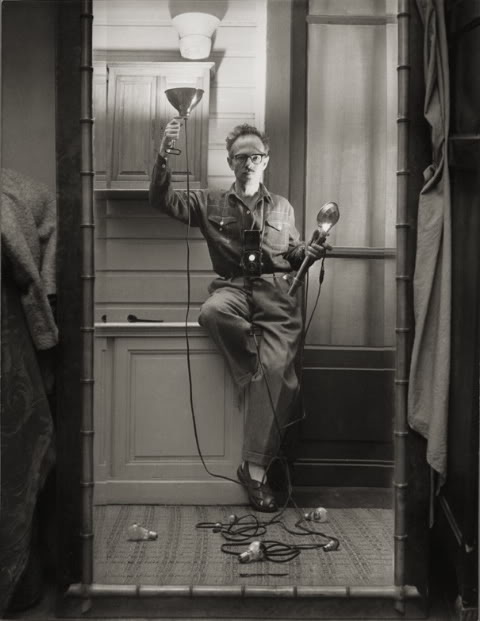

The third image, Self Portrait with Flash (1951) shows Ronis in a different light. At this stage in his career he had worked as a freelance photojournalist. He had covered workers disputes and had developed a strong self of social justice. He is quoted in the exhibition “We must work to change this world and make it better”.

This image shows Ronis in his studio holding a flash. He is now dressed in clothes suggestive of a working man, rather than the suit of the previous image. He also adopts a quirky pose on one leg and it is this that adds a sense of light heartedness to the image compared to the seriousness of the two previous ones. Does this reflect the greater self confidence of an established freelancer with international publication – he chooses how he wants to show himself, rather than how he thinks others want to see him.

The fourth image, Self-portrait L’Isle sur la Sorgue 1978, continues this theme of him portraying himself as the established successful photographer.

He is sat at his desk, studying a negative. The desk appears to be covered in the clutter associated with this position. I suspect it is carefully arranged and selected to show different aspects he wants to show. His diary is open in front of him – a diary of appointments will determine his activities and has a great importance in his life. There are collections of negatives and mounted slides, documents and journals in foreign languages reflecting his international status. A large treble clef is drawn on a page, part covered by other clutter – is this a memory of his original career plan, it appears incongruous otherwise.

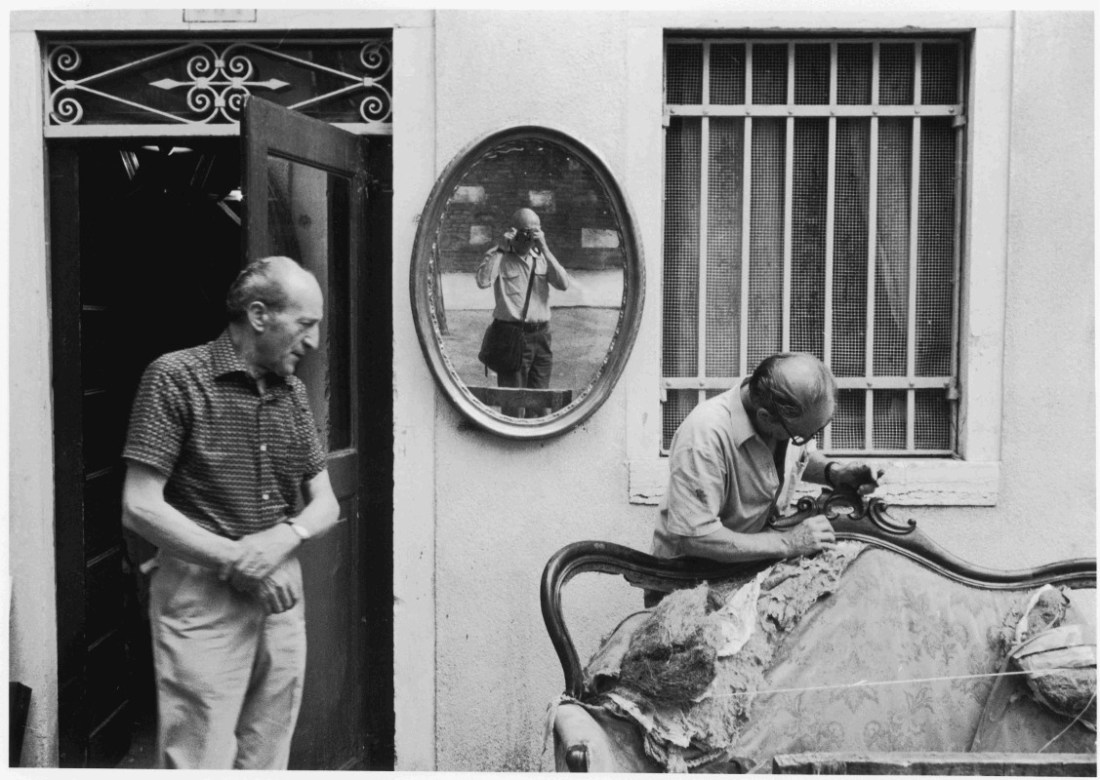

The final image is from Giudecca, Venice in 1981. He describes it as a “discrete self-portrait” as the image appears to be of upholsterers outside their workshop, but Ronis can be seen clearly in the centre of the image, reflected in a mirror on the wall.

Ronis is seen, casually dressed, with his camera bag and small camera. He appears as what he started out as, a street photographer. He is not taking a large part in this image, which remains that of the upholsterers and otherwise looks like one of his early images from Paris. His presence is discrete – as it needs to be for a street photographer. I consider that this reflects Ronis portraying himself as how he started and how he wanted to be seen towards the end of his career.

4. Other learning points

There were many other aspects to this exhibition which influenced how I looked at these images. Many of them made me consider the “Decisive Moment” and I will refer to these in my account of Assignment 3 “The Decisive Moment”.

A further aspect to many of Ronis’s works is the sense of humour. I have mentioned this in relation to his Self-Portrait with Flash, however there are many more images which one cannot look at without smiling.

5 thoughts on “Willy Ronis: Photographies 1934-1998 Casa dei Tre Oci, Venice December 2018”