Don McCullin – Tate Britain

February 2019

I visited this exhibition of McCullin’s work soon after it opened. The Tate website describes the exhibition as:

“Spanning sixty years of photography and world events, this exhibition begins in and around the London neighbourhoods where McCullin was raised. It moves into his coverage of conflict abroad, interspersed, as his life has been, with sections covering his trips back to the UK. The exhibition ends with his current and longstanding engagement with traditions of still life and landscape photography.”

There is a huge amount of material presented in this exhibition. The subjects are varied from his early work in around his family home in London, his coverage of conflict abroad and in Northern Ireland, the urban conditions in the industrial UK, and his still life and landscape images in the UK and overseas.

As I have done with other exhibitions, I have summarised here my key impressions and learning points, rather than try and encompass the whole exhibition. Some of these expand on ideas I already raised in my account of the TV programme, Looking for England.

1. Motivation

The exhibition of images from Bradford and the east end of London show McCullin’s concern with social inequalities and the conditions of the urban poor. I described this in my reaction to the “Looking for England” documentary.

In the exhibition notes is a quote from McCullin summarising his concern.

‘There are social wars that are worthwhile. I don’t want to encourage people to think photography is only necessary through the tragedy of war.’

While this is obvious in his documentary depictions of the living conditions of people in Bradford and the East End.

I thought his early work also showed this concern.

This image of boys boxing puts the title subjects in the distance. Predominance in the image is the accumulation of rubbish in the road seen in the foreground. McCullin appears to be showing that boys play in the street here surrounded by this squalor.

Although he clearly has these views about inequality, he has throughout his career covering conflict McCullin has insisted on his own neutrality. In the exhibition was his statement of his position:

“No one was my enemy, by the way. There was no enemy in war for me. I was totally neutral passing-through person.”

2. Darkness in his images

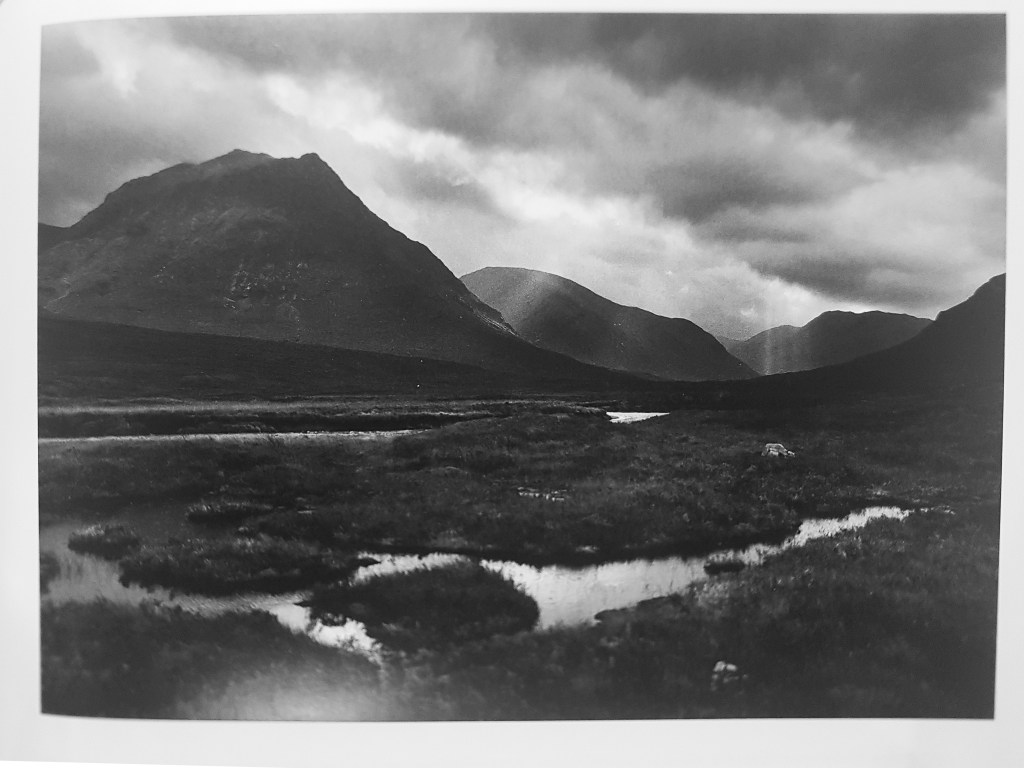

In “Looking for England” McCullin says “I cannot help taking my prints darker and darker and darker, I don’t know what makes me do it”. His images of English and Scottish Landscapes are dark – the skies are darker than would be the case in life. This gives a brooding threatening sky and land.

McCullin himself compares these to war zones.

“You can see in my landscapes the dark Wagnerian clouds, which I darken even more in my printing, the nakedness of the trees and the emptiness, which make the earth look as if it had been scorched or pulverised by shells.” (Don McCullin. Mehrez A Ed. Tate 2019. p155).

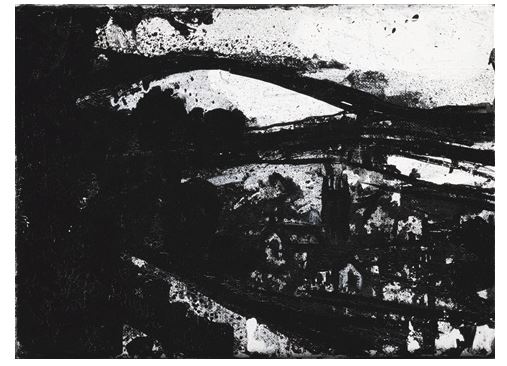

The large expanses of black in many of his images reminded me of the landscapes of John Virtue. I was directed to the work of John Virtue by my tutor. Virtue is a landscape artist who uses only black and white on his work; he uses shellac black ink and white paint.

The landscapes become abstract in this medium but the quality of the image is very like that of the McCullin landscapes.

3. Emotional contact with subjects

In many of his images McCullin establishes contact with the subject by them making eye contact with the camera. This is in the same way as I commented about Willy Ronis’s work.

For example we can see this clearly in this image of the Aldermaston demonstrations in early 1960’s

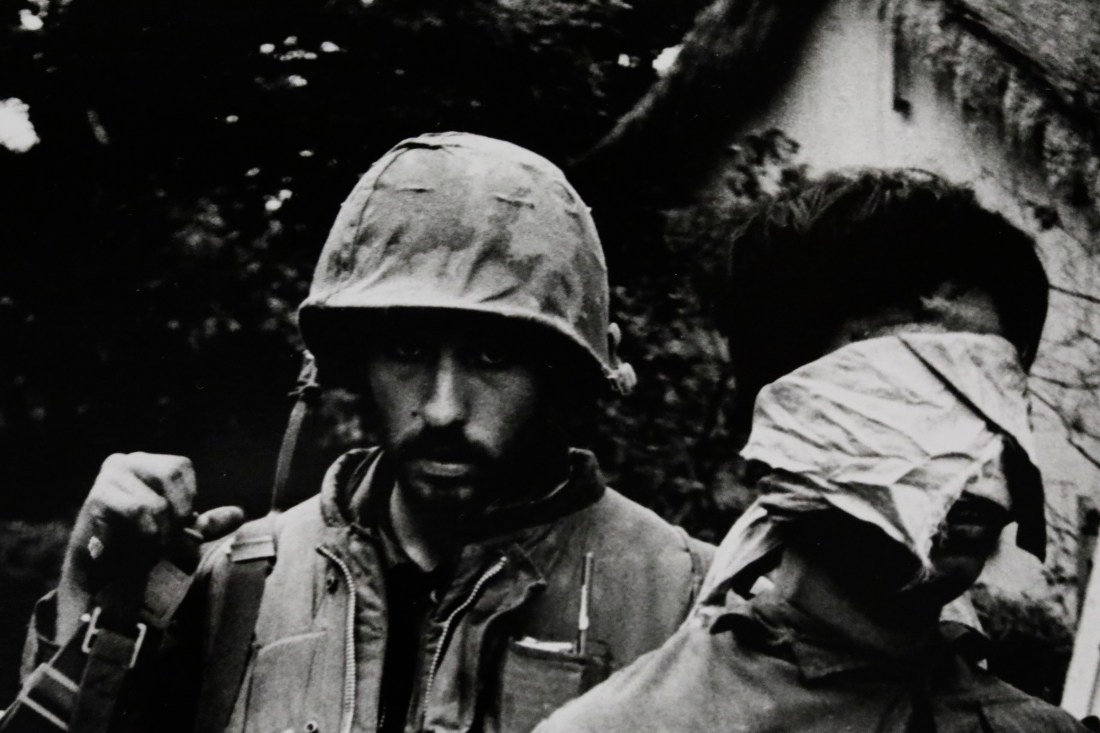

However I noted that in some of his war photography, it becomes more difficult to see the main subjects eyes and establish this same type of contact and I would suggest, empathy. These images from Vietnam taken in 1968 show the US marines’ eyes to be in the shadow of their helmets and difficult to see.

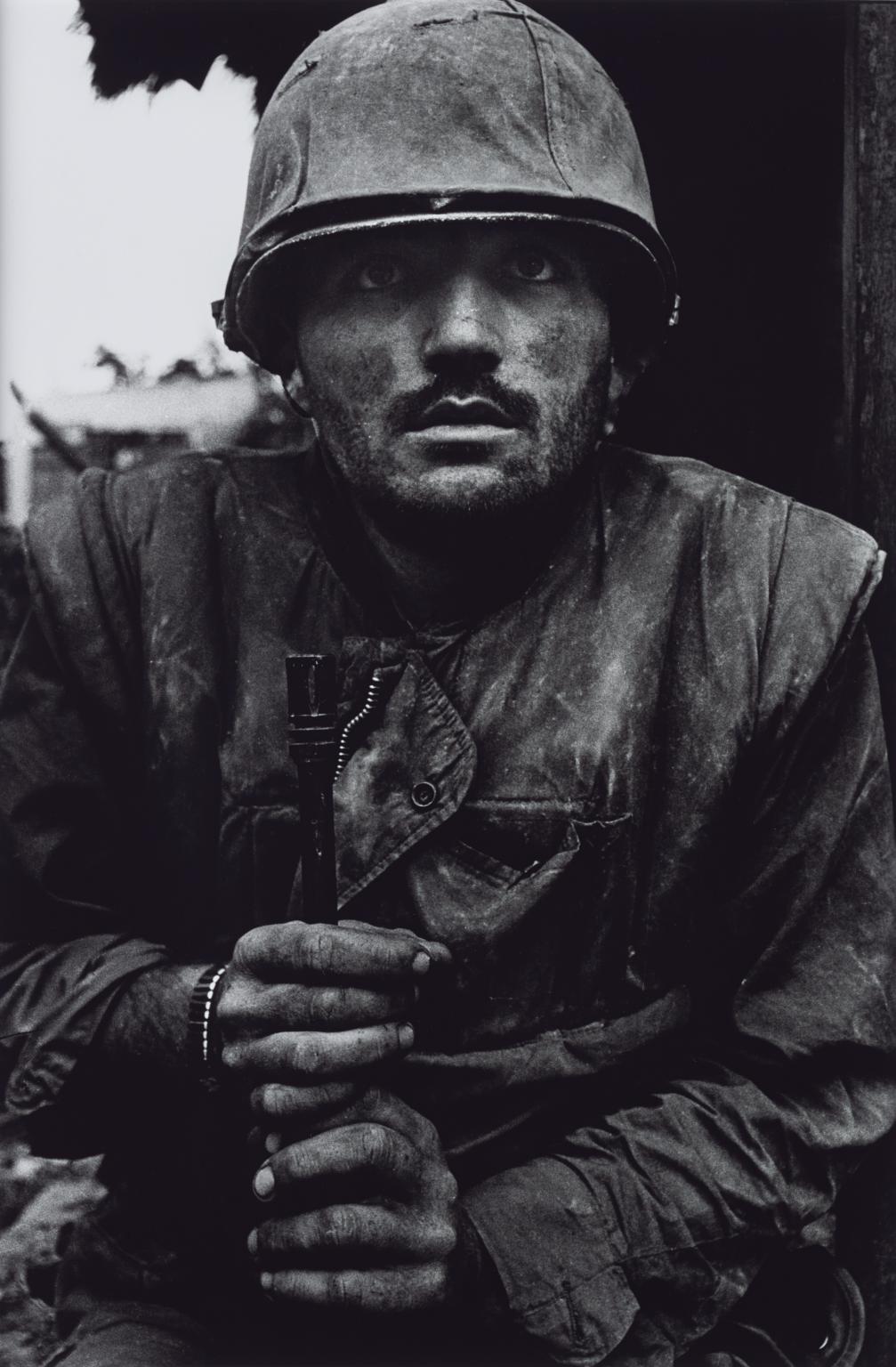

This is in contrast to earlier images such as this taken three years earlier in 1965, where we can clearly see the eyes of the soldier.

This made me wonder if after three years of the Vietnam war, McCullin is in some way distancing himself from the emotional contact with his subjects. Having experienced the events of the war and witnessed the effect on the soldiers and civilians, I would be surprised if this did not have an effect on him.

The effects of combat stress on military personnel is well known and McCullin records it in this image of a “shell-shocked” US marine (my italics).

Descriptions of this soldier’s condition made by people around him at the time are described in a newspaper article by Antony Loyd ( Shell-shocked: Anthony Loyd goes in search of the Vietnam War veterans photographed by Don McCullin. The Times, February 23 2018). Loyd summarises these:

“The Marine was swallowed by the night. When he was found he was mute, though in his eyes lay a stare best unmet while dreaming: a gaze that was part trance, part fear, but mostly horror. The men who had located him recall that he neither blinked nor uttered a single word.”

He quotes McCullin as saying

“I noticed he was moving not one iota. Not one eyelash was moving. He looked as though he had been carved out of bronze. I took five frames and I defy you to find any change or movement in those frames.”

and his colleagues

“He was in a state of shock. He had the classic thousand-yard stare, and was kind of frozen.”

“I thought someone had cut his throat, the way he looked. Because I’ve seen people with their throats cut and their eyes just wide open.”

The navy corpsman, a medic, who examined him is reported as saying to the sergeant in charge:

“Sarge, his mind is not there. We need to get him out of here.”

These are classic descriptions of recognised mental disorder, specifically Acute Stress Reaction (ICD-10 F43.0) followed by a Dissociative Stupor (ICD-10 F44.2) and I have included fuller descriptions of these in another post, International Classification of Diseases (ICD-10) – Reactions to Stress.

The effects of psychological stress on combatants is well recognised and steps are now taken by armed forces to mitigate these. However others who witness these events are also susceptible to stress reactions, and I wonder if McCullin himself has been affected by this.

The risks of physical harm to journalists covering conflict has been recognised in the film A Private War, 2018, describing the career and death of war correspondent, Marie Colvin. Indeed McCullin himself has been injured on several occasions and the Tate exhibition includes a camera body he was carrying, in which is embedded a bullet.

The psychological consequences of working in a war zone and/or witnessing massive humanitarian crises are less well recognised in journalists. What is even less recognised is the effect this then has on the types of image produced by photographers subject to this stress.

The Tate exhibition includes a quote from McCullin regarding him being asked to cover the Iran-Iraq war in 1991.

“I hadn’t covered a theatre of war for seven years since leaving the Sunday Times and felt mentally ill-equipped for the assignment I had suggested to the Independent newspaper. It felt like tempting providence once too often. I began to wish I wasn’t there when I saw the burnt and injured children and in some respects, I wish I hadn’t gone. The immorality of the situation seemed intolerable. Did I need to face all this yet again?.”

He is clearly describing mental distress at his situation and having to witness the events. Furthermore he describes longer-term sequelae.

“Sometimes when I’m walking over the Yorkshire moors or in Hertfordshire, the wind rushes through the grass and I feel as if I’m on the An Loc road in Vietnam hearing the moans of soldiers beside it. I imagine I can hear the 106-mm howitzers in the distance. I’ll never get that out of my mind” (Don McCullin. Mehrez A Ed. Tate 2019. p154).

These sound like episodes of “repeated reliving of the trauma in intrusive memories (‘flashbacks’)” a characteristic feature of Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (ICD-10 F43.1).

Is it this psychological reaction to what he has witnessed and his memories which initially made him want to distance himself emotionally from the protagonists as shown by lack of clarity of the soldiers faces in later images of Vietnam, and now make him produce such dark images of the British landscape?

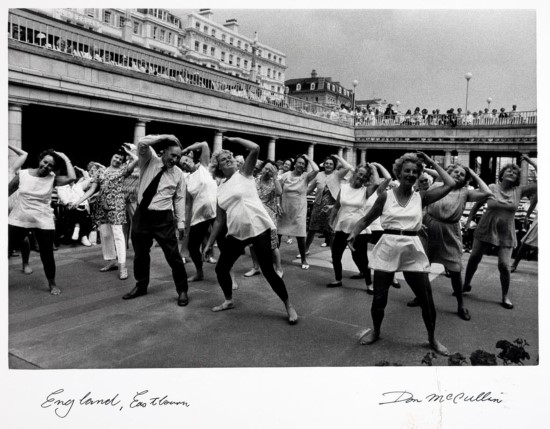

However it is easy to categorise McCullin’s work as dark and harrowing. There is a lighter side to his work perhaps exemplified by this image of a dance class in Eastobourne.

In the documentary, Looking for England, he revisits this site of this image and clearly enjoys the incongruity of the sight of people enjoying a brass band in the pouring rain.

https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/p06zlny1/player

He makes jokes about people going to the beach in the wind and rain. Overall, he does not seem a overly preoccupied with the horrors he has seen over the years, but is enjoys his interest in people and their activities. I wonder if it is from this that his sense of justice stems, when he sees inequalities or brutality to which he needs to draw wider attention.

4 thoughts on “Don McCullin – Tate Britain. Feb 2019”